Interviewer Krista Vavere

To be dissatisfied with life – this takes away our strength. But dissatisfaction can stir us to open to something valuable. Elga Rusins and Margarita Putnina in their time have tossed away everything, in order to say “Ï’m happy”.

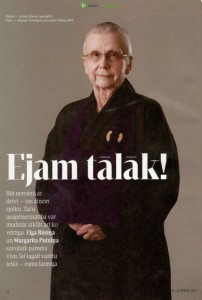

EVERYTHING MAKES HER HAPPY

Elga Rusins (spiritual name Bridin) greets me on the entryway steps in a brown monks robe with “sveiks” and holding her palms together. In the next moment she reveals “I am happy here”. We are standing in the entryway to her apartment, so I ask if that refers to this apartment or life in general. That refers to everything. Everything that Elga talks about she conside rs wonderful: the opportunity to be in Latvia; the chance to say in Latvian those things she has thought about for years in English; that strangers know how to pronounce and spell her name; that 12 people came for her first retreat in Riga; that she swims in a school building where her brother was a student 70 years ago; and that she often passes the house where her parents lived at one time. “Life in Latvia – that is a gift”. Everything here gives her joy – so that the decision to move from the USA at age 70 was right.

rs wonderful: the opportunity to be in Latvia; the chance to say in Latvian those things she has thought about for years in English; that strangers know how to pronounce and spell her name; that 12 people came for her first retreat in Riga; that she swims in a school building where her brother was a student 70 years ago; and that she often passes the house where her parents lived at one time. “Life in Latvia – that is a gift”. Everything here gives her joy – so that the decision to move from the USA at age 70 was right.

Entering the Zen Buddhist world of Elga’s apartment starts with a strong smell of incense. Elga shows me Buddhism’s Soto Zen “ancestral” tree, photographs of teachers and the compassionate goddess Avalokiteshwara’s statue, which she once found in a parking lot in New Jersey. “We were both at that time bottomed out.” Elga herself fixed the statue’s torn back and painted her. The statue, as well as Elga, started a new life.

Elga’s becoming a monk was not a continuation of a fanatical religious life, rather it was the answer to a question of many years duration “Is that all there is to life?” In her life she had everything, but this “everything” led to a longing for more. “In the beginning I thought – I’ll go to college and get a good job. Then I thought I’ll get a Master’s degree. Got it. Then it would be good to be married: everybody needs a family life and children. Got married. I had a child. It was wonderful. But is there something else? I wasn’t completely satisfied. Maybe I should live alone? Maybe I need to get rich, dress well, look good? I’ll try to be beautiful. I thought that this would make me feel good, but this also didn’t work out…This is Buddha’s teaching, that in this life we never have enough of worldly things.

WAS NO HOLY ONE

“I lack the spiritual capacity to believe in anything”, so Elga thought, when she was not able to feel at home in any religion and satisfy her spiritual interests. She practiced Yoga for 25 years, developed her own religion, which incorporated bits of various religious teachings. She took advantage of every opportunity to be in silence, often going on retreats, at times settling into a friend’s empty house, and then returning to a worldly family life. Buddhism seemed strange to her, until a colleague gave her a book to read. She accepted the book out of politeness, but reading it made her think.

Elga’s work life was spent in New Jersey in social work with abused women and older adults. After 25 years she thought she would change her life. Move to Latvia? Do something else? Seeking answers to these questions, Elga decided to spend a month in a Zen Buddhist monastery in quietness in California. “I felt it in my bones – not here (she points to her heart) and also not here (she points to her head), but in my bones, that these teachings, which the monks gave, were real, that there was that truth in them. That was unexpected.” A month in the quietness didn’t answer the question of what to do with her life. It gave another direction: enter monastic life. This thought was a shock: “I was not the monk type. I was a person of the world. A “holy one” I never was.

Elga was three months old, when her family fled to Germany in 1944 as refugees and later to the USA. When her marriage fell apart in the 90’s, Elga came to Latvia for three months and made a decision here – to return to the US, at the age of 55 to enter a Zen Buddhist monastery. Entering takes 2 years. “I asked monks: why did you become a monk? They said: I can deepen my practice in this way, I don’t have responsibilities for other things: payments, a car, what to wear today, how to fix my hair. I also spoke with people who only practiced in the monastery. I asked why they didn’t enter monastic life. The answer was that it was too limited. I thought: If I’m going to do so something this big, that changes my whole life, then I’ll opt for the deepest practice and see if it works out. I’ll jump into the deep water, we’ll see if I swim.”

Elga shows a photograph which shows the monastery’s meditation hall. At night that becomes a monk’s sleeping space. Strips mark the boundaries of one sleeping place’s designated width. A sleeping space is about a meter wide and almost two meters long, a small cupboard for underclothes and a thin mattress – that is all the private space a monk gets. Crossing over the lines is not allowed – that means you are violating another person’s territory. This teaches a simple lifestyle, the ability to get by with little and to get along with others. “That is freedom. You learn that things and comforts are not important. You learn not to grasp. That is hard, but possible. These teachings are given so that monks are prepared for all of life’s circumstances. How you can get by in a life where you cannot choose a single thing: not what to eat, not what to wear, not when to get up, not what you are going to do. This all has to be taken for the good. When you learn that, it is liberating.”

ASSIGNMENTS YOU DON’T KNOW HOW TO FULFILL

In the monastery, only a part of the teaching is reading and understanding texts. The hardest teachings are built into everyday life. This doesn’t get explained. No one is promised any gains from learning to sleep in a small space with other people, learning to concentrate and let go of other thoughts and interests. Some teachings Elga only understood when she left the cloister walls, some she is seeing for the first time as we are having this conversation. “You have to live wholeheartedly, as much as you can. That is the monastery’s teaching. If someone doesn’t know how to work in a garden, he’s told “You’ll be the garden supervisor!” “What, me?” “You will lead the chanting tomorrow.” “Who, me?” “Now be in the loft and hit the gongs correctly.” “I don’t know how!” “You need to sew three robes before ordination!” One poor novice was given the job of fixing washing machines. I saw her sitting on the floor with papers, all the parts are out, she is looking in a book for how to fix the thing. She was successful. If you don’t know how to do something, sit down, look with a quiet mind at what is there…. I myself put in a toilet. Not alone, but with another person. I didn’t know anything about pipes and plumbing, but it worked. You get a feeling of confidence from this, that you can accomplish something. Also, if it doesn’t work out, there is teaching in this. It is not as if: oh, she failed. She tried her best, and it didn’t work out. You have to go forward without fear.”

Elga calls the years spent at Shasta Abbey in California’s mountains a difficult and wonderful opportunity. Her assignment was to fix her mind on life on Zen Buddhism, but after 15 years Elga became certain, that she had to go to Latvia. “Latvia has been calling to me for years. I don’t understand this rationally. I feel it.” Receiving permission to live and work in Latvia, she wears monks’ clothes and lives in a practiced daily rhythm, adding that there is a little more time to sleep, exercise, and read books.

Returning to Latvia, which had never really been a known place, Elga dared to start a new life. She doesn’t know if there are people here who will be interested in Zen Buddhist teachings, meditation and retreats. But her experience gives her strength, “In this life, we are in a process, which never has an ending point. We are always evolving and with deeper awareness going on to the next thing. In the retreat (Elga’s first retreat led in Latvia) I translated the Heart Sutra. At the end is a mantra, which translated reads like this: “Going, going, always going on! Always becoming Buddha.” We are changing every moment. Our job in this life is to develop, in our own circumstances, the highest awareness and mind. That is the spiritual practice! And it doesn’t stop. When life is hard for me, and in America I had big fears: what have I taken on, don’t know how things will be in Latvia, if I will have enough money, how I will get by with the language, I’m old, maybe I’ll get sick, I sang this mantra to myself “Going on Beyond”.